He Didn’t Just Witness History, He Helped Heal It.

- Augusta Bangura

- Sep 1

- 4 min read

Updated: Sep 3

By: Augusta Osmatu Bangura

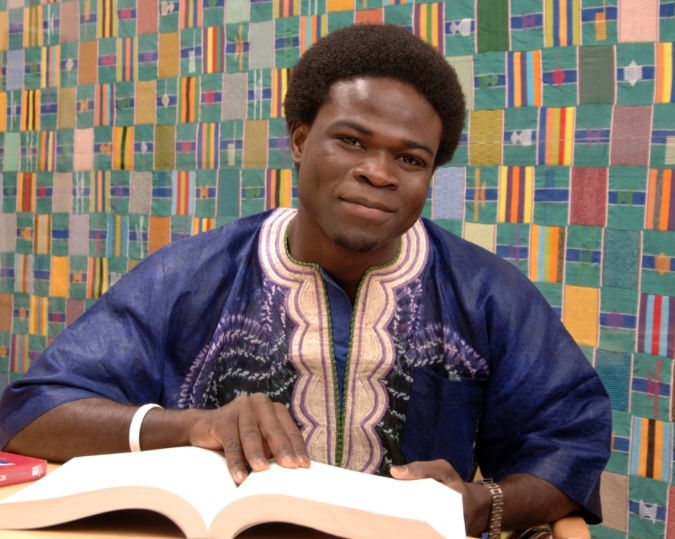

There they were, begging on the streets of Freetown. No one stopped. No one really saw them. They hovered between visibility and invisibility, present yet forgotten, as if the nation had agreed to look away. The war was over, and with it, the memory of its survivors. But one person stopped. He met their eyes. He listened to their stories. Joseph Ben Kaifala didn’t just listen, he built a platform where their voices could be heard, a way to keep the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendations alive. For him, remembering was not about dwelling on the past but ensuring the nation could truly heal and never repeat its darkest tragedy.

At the end of Sierra Leone’s brutal civil war in 2002, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission left behind an unfinished task: victims still cried out for reparations, and whole communities were haunted by graves that had never been properly honoured. As a young student, Kaifala was struck by the sight of amputees — people who had borne the worst of the war — reduced to beggars while passersby ignored them. “It was appalling,” he recalls. “Nobody was doing anything. Even as a student, I couldn’t accept that.”

From that outrage, he founded the Center for Memory and Reparations, an institution dedicated to preserving history and healing communities. Its mission rests on three pillars: mapping and protecting mass graves, teaching young people about the causes of the war, and amplifying the voices of survivors who continue to demand justice. For some, it may look like “dwelling on the past,” but Kaifala insists otherwise: “I am dealing with the past in the present, and rectifying errors for the future.”

One of his most powerful moments came in N’Jala, Kono, where he supported villagers in giving their dead proper traditional burials. Skeptical about whether the work mattered, he asked the local chief. The chief’s reply changed him: “You wouldn’t understand how important this is. We believe the terrible things that keep happening in our society are because we did not give our people a proper burial. Perhaps now we will have a better community.” In that moment, Kaifala realized he was not just recording history; he was facilitating healing.

Kaifala’s vision, however, extends beyond memory. Through the Jeneba Project, he built one of Sierra Leone’s first tuition-free schools for girls, eliminating barriers like uniforms, fees, and textbook costs that often kept them at home.

He calls it the Sengeh Pieh Academy, “an educational safe space” where girls can focus on learning, free from the burdens of daily struggles. His advocacy for free, quality education, once a dream, is now national policy.

At the same time, his work through the Center for Memory and Reparations keeps the TRC’s recommendations alive, moving them toward implementation — lifetime healthcare for amputees, men and women once abandoned to the streets. It called for HIV testing and treatment for rape survivors, many of whom carried both visible and invisible scars. It urged skills training, pensions, microcredit programs for vulnerable groups, and scholarships for children whose education was cut short by war. The state has too often failed to deliver, but Kaifala’s work keeps those commitments alive.

His voice, his projects, and his persistence remind Sierra Leone that justice delayed is not justice denied, ensuring the promises of healing and support actually reach those who need it.

“What we have done over the years is at least create a platform where people can openly discuss their trauma as a beginning, and also to ensure that many young people in this country understand the Sierra Leone civil war and why we went to war in the first place,” he stresses. “Because unless we understand those things, we will continue to repeat the errors that led us into conflict.” His greatest measure of success, he says, is knowing he is shaping the next generation of leaders. “When these leaders are aware of where their country has been, perhaps they’ll make better choices… they will do everything within their power to avoid these errors.”

Yet what truly makes Mr. Kaifala extraordinary is not only that he stood up for the victims of Sierra Leone’s civil war or built a school, but that he also chose to stand up for those we might rather forget: the perpetrators.

For him, the line between victim and aggressor is blurred. A child forced into combat at seven, made to kill at twelve, made to rape at fourteen — is that child only a monster? Or is he also a casualty of a war that devoured innocence? Kaifala believes the answer is both. “They were victims as well,” he insists. “By conscripting a child into a combatant role, you are violating that child’s rights. They were forced to become perpetrators and were both victims and perpetrators. We are responsible for all of that as a society.”

It’s a radical kind of compassion, one that unsettles at first, because why help someone who has inflicted so much pain? Why give a second chance to someone who took lives? Kaifala insists that healing cannot be selective. “Every Sierra Leonean was affected by the war,” he says. “If these people are still suffering, we ought to help them without discrimination. A bunch of unwell people cannot build a nation.” His life’s work, then, is to make Sierra Leone well again.

That conviction was born not in government halls or international conferences, but in the heart of a student thousands of miles away. As a teenager studying abroad, he didn’t do what most might: simply sighed at the tragedy.

Kaifala decided to act. But if you call him a hero, he shrugs. “I don’t think anyone walks around calling themselves a hero. That is the habit of hubris. I simply made the choice to serve,”he says. And yet, in serving quietly, relentlessly, and selflessly, Mr. Kaifala has become exactly what he resists being called: a modern-day hero.

Comments